Rewiring the Brain

New research reveals how psychedelic compounds restore synaptic connections lost to chronic stress—and why their therapeutic effects may last for months

The human brain contains billions of neurons, each sprouting elaborate branches that reach out to communicate with neighboring cells. These connections, formed at specialized junctions called synapses, create neural circuits underlying everything from memory to decision-making. But chronic stress quietly dismantles this intricate architecture, stripping neurons of dendritic spines, the tiny protrusions where synapses form.

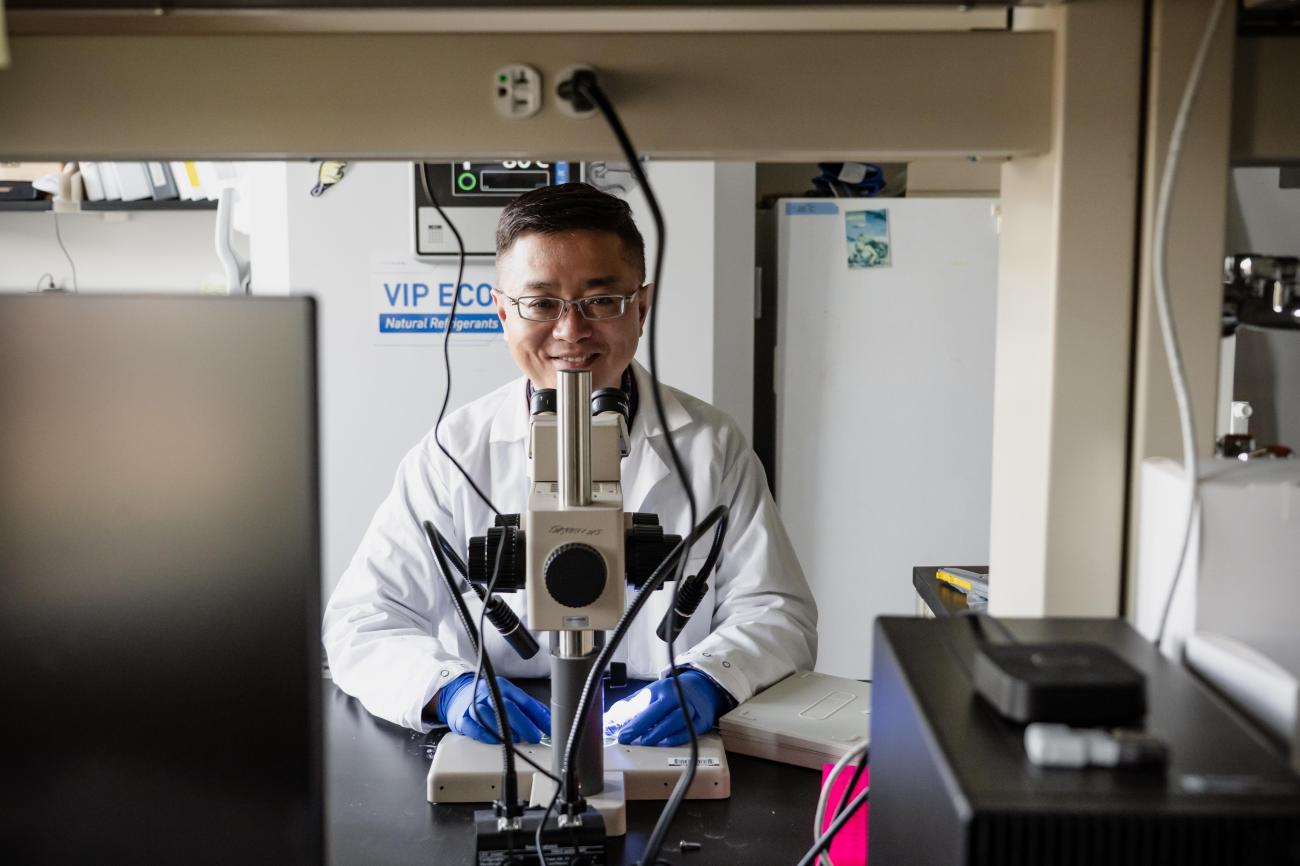

Now, emerging research suggests that psychedelic compounds may help rebuild these damaged circuits, offering new hope for treating depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and other stress-related conditions. Neuroscientist Ju Lu focuses on this line of investigation in his laboratory, using advanced brain imaging techniques to observe this repair process in real time.

Psychedelics represent a class of hallucinogenic chemicals united by a common mechanism, the activation of serotonin 2A receptors in the brain. While all classical psychedelics — including psilocybin, LSD, and DMT — bind to these receptors, the relationship between receptor activation and hallucination remains puzzling. Some compounds that specifically target these receptors produce no hallucinogenic effects whatsoever, suggesting additional complexity in their pharmacology.

Despite their controversial history, psychedelics have attracted renewed clinical interest following small-scale trials showing efficacy against treatment-resistant depression. Unlike conventional antidepressants such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which patients must take continuously, psychedelics appear to produce lasting benefits from just one or two doses administered in a therapeutic setting. Follow-up studies document sustained improvement six months to a year after treatment — a stark contrast to SSRIs, which often lose effectiveness when discontinued.

Modeling Stress in the Laboratory

The requirement for clinical administration and the hallucinogenic experience itself present practical obstacles to widespread therapeutic use. Lu, assistant professor of biological sciences, is continuing studies he started during his postdoctoral work at University of California–Santa Cruz with Yi Zuo, professor of molecular, cell, and developmental biology. Their collaborator, Dr. David Olson, a chemistry professor at University of California-Davis, has developed a new compound called tabernanthalog (TBG), which is similar in structure to the psychedelic drug ibogaine but lacking its toxic and hallucinogenic effects. In a collaborative study, they found that a single dose of tabernanthalog (TBG) could rapidly reverse the effects of stress in mice. The drug can correct stress-induced behavioral deficits, including anxiety and cognitive inflexibility, promote the regrowth of neuronal connections, and restore neural circuits in the brain that are disrupted by stress.

On the behavioral level, stress causes increased anxiety, deficits in sensory processing, and reduced flexibility in decision-making. In the brain, stress disrupts the connections between neurons and alters the related circuitry, resulting in an imbalance between excitation and inhibition. In recent years, there has been renewed interest in the use of psychedelic substances for treating illnesses such as addiction, depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. However, the hallucinogenic effects of these drugs remain a concern, and scientists have been unsure whether the hallucinations are therapeutically important or just a side effect. TBG has not yet been tested in humans, but it lacks the traditionally used psychoactive drug ibogaine’s toxicity in animal tests, and it doesn’t induce the head-twitch behavior in mice caused by known hallucinogens.

Although TBG hasn't entered official clinical trials, there are some personal accounts of its effects. In 2023, research scientist Arthur Juliani documented his own experience taking 150mg of TBG. He described a nine-hour period of intense focus and calmness—which he termed "psychedelic attention," but without the visual distortions or emotional shifts common with traditional psychedelics. Juliani argued that TBG does produce significant mind-altering effects that might be necessary for therapy, raising questions about whether the subjective experience can truly be separated from psychedelic treatment.

With the Zuo lab, Lu and his coworkers tested whether TBG can reverse the neural damage caused by chronic stress. He exposed mice to seven days of unpredictable mild stressors, uncomfortable but non-painful conditions such as cage tilting, loud music, social isolation, or "island isolation," where mice stand on small blocks surrounded by shallow water. This regimen mimics the unpredictable nature of real-world stress without causing physical harm.

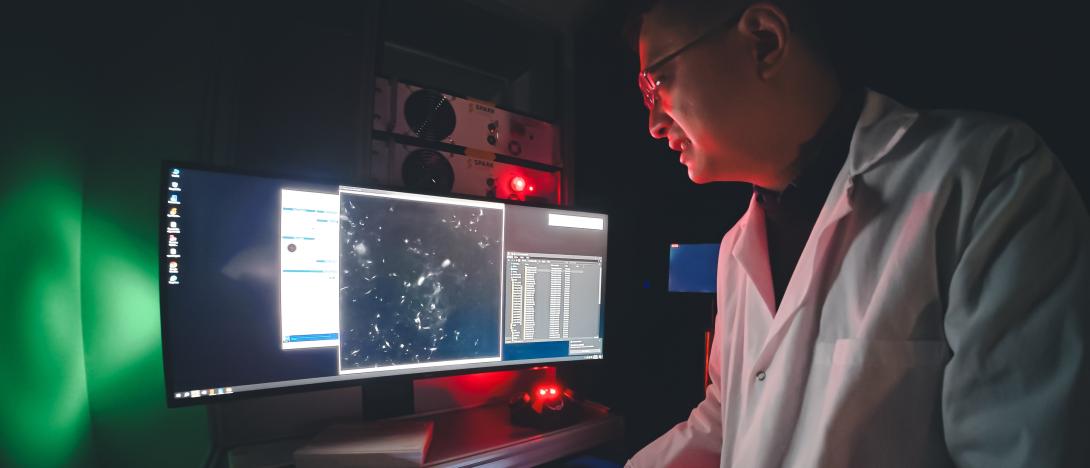

To observe the brain's response, Lu employs two-photon microscopy, a sophisticated imaging technique that can peer deep into living tissue. Unlike conventional microscopy, which produces a bright blur when imaging thick tissue, two-photon microscopy uses powerful infrared lasers. Each fluorescent molecule must simultaneously absorb two low-energy photons to emit light, an event so improbable that it occurs only at the microscope's precise focal point. By scanning this point across brain tissue, researchers can build high-resolution images of neural structures.

Documenting Damage and Repair

The imaging revealed extensive synaptic loss after seven days of stress. Numerous dendritic spines that had been present vanished, disrupting the prefrontal cortex circuits essential for working memory, executive function, and decision-making. Without treatment, few new spines formed in the following 24 hours. But a single injection of TBG dramatically accelerated synapse formation. New spines appeared where old ones had been lost—not in all locations, but at rates substantially higher than baseline. The drug clearly facilitated circuit restoration, Lu says.

“If you give the drug, you see quite a bit of the formation. One dendritic spine was lost and then two of them formed,” he says. “Another is lost; one is formed. So, the statistics show that over one day, the formation rate is much higher than in the baseline condition, or after stress where the spine has recovered.”

The behavioral consequences proved equally striking. The team documented three stress-induced deficits using standardized tests. First, anxiety increased, measured by reduced time spent exploring the open arms of an elevated maze. Second, cognitive flexibility declined dramatically. Mice learned initial tasks normally but struggled to adapt when rules changed—they became "stubborn," unable to forget old associations and learn new ones. Third, sensory processing deteriorated. Control mice naturally prefer investigating novel textures over familiar ones, but stressed mice lost this discriminatory ability entirely. A single dose of TBG restored normal behavior across all three measures.

The Neural Noise Problem

Lu’s research expands from structural brain changes to explore how stress disrupts neural activity patterns. Using fluorescent proteins that light up during neuronal firing, he observed that stress doesn’t merely suppress activity — it increases background “noise.” In healthy mice, neural signals in sensory-processing regions tightly align with whisker movements, their main exploratory behavior. Under stress, this coordination breaks down: neurons remain active but fire erratically even during rest, collapsing the signal-to-noise ratio. Treatment with TBG restores normal patterns by quieting inappropriate neural firing. Similarly, when mice perform texture discrimination tasks, control animals show neurons that respond selectively to familiar or novel textures, while stress erases this selectivity. Again, TBG reinstates distinct neural responses.

In a related line of work, Lu and collaborators examined how psilocybin’s therapeutic and hallucinogenic effects diverge at the cellular level. By manipulating serotonin 2A receptors in specific neuron populations, Lu and his colleagues found that removing these receptors from specific neurons blocks synapse formation but not hallucinatory “head-twitch” behavior. Restoring the receptors only in these neurons reinstates synaptic plasticity without inducing hallucinations. Thus, receptor activity in certain neurons is essential for therapeutic plasticity but unrelated to psychedelic effects. This dissociation suggests that psychedelics like psilocybin act through multiple pathways, raising the possibility of developing new compounds that enhance neural plasticity without hallucinations — though whether such separation retains full clinical benefits remains to be seen.

The Persistence Question

One crucial question concerns durability. Clinical studies show that psychedelic therapy produces benefits lasting months or years, yet Lu's initial experiments examined only acute effects over one or two days. Follow-up research addresses this characteristic. The data reveals a temporary burst of synapse formation — formation rates return to baseline levels within a week. However, preliminary analysis suggests that synapses formed during this drug-induced window survive at higher rates than those formed through normal fluctuations. If confirmed, this enhanced stability could explain long-lasting therapeutic effects. The circuit modifications persist even after the drug's direct effects fade.

What makes these drug-induced synapses more stable remains unclear, but Lu speculates they may receive different patterns of input or possess distinct molecular properties. Understanding this mechanism could reveal why neural circuits malfunction in depression and related disorders, potentially enabling more targeted interventions.

“We're still analyzing this data, but it seems like although this formation itself is a kind of transient boost, these new synapses tend to stay longer. And we think that probably something has to do with the fact that the therapeutic effect is long-lasting, because they stay, and therefore the circuit is permanently changed that way, more persistent. And now the question is, we know they're mostly expressed in these layer five neurons. So, what if they get rid of them from there? What would happen?”

The research carries important implications for developing next-generation treatments. If therapeutic benefits arise from lasting circuit modifications rather than acute drug effects, optimizing synapse stability may matter more than maximizing initial formation rates. The separability of hallucinogenic and neuroplastic effects suggests that compounds could be engineered to favor one over the other.

Lu's research trajectory aims toward understanding not just what psychedelics do but how they do it at cellular and molecular levels. Which genes activate in newly formed spines? What patterns of neural activity predict whether synapses will stabilize or disappear? Perhaps most importantly, this work exemplifies how studying the mechanisms of psychoactive compounds can reveal core principles of brain function. The circuits that chronic stress dismantles, and psychedelics repair participate in the essential human experiences of mood, memory, and perception. Understanding their dynamics brings us closer to treating their dysfunction and, ultimately, to comprehending how our brains construct the reality we inhabit.